A 9-year USFS aerial firefighting study left many questions unanswered

The raw data has not been released

In fiscal year 2018 the U.S. Forest Service spent more than half a billion dollars, $507,000,000, on air tankers, helicopters and other firefighting aircraft.

The agency’s spending on aircraft contracts, support, and fire suppression operations has gone on for decades with little meaningful oversight. The Forest Service has been repeatedly asked to justify the expense by the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Agriculture’s Inspector General, and Senators and Representatives in committee hearings — “How do you know air tankers are effective?”

A report by the GAO in August, 2013 said, “None of the agencies’ studies and strategy documents contained information on aircraft performance and effectiveness in supporting firefighting operations, which limits the agencies’ understanding of the strengths and limitations of each type of firefighting aircraft and their abilities to identify the number and type of aircraft they need,”

The Inspector General’s investigation concluded, “[The Forest Service] has not used aviation firefighting performance measures that directly demonstrate cost-impact…”

In 2012 the Forest Service began the Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness (AFUE) study to address those concerns. After nine years and an annual cost of $1.3 million plus overtime for the field data collectors, a report about the study was quietly released August 20, 2020 during the peak of an exceptionally busy wildland fire season.

The AFUE had very ambitious goals initially when Tom Harbour was the Director of Fire and Aviation for the U.S. Forest Service.

“AFUE was initially intended to eventually help answer questions about the size and composition of aviation assets needed by the USFS,” Mr. Harbour told Fire Aviation recently.

From the agency’s AFUE website:

The desired outcome is to support training, mission selection and execution, and overall aerial fleet planning to enhance effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, potentially reducing aviation and fire suppression costs by answering a general, but complex question: “What are the best mixes of aircraft to do any fire suppression job?”

The data in the study was collected by four crews, or modules, of three to four single resource qualified firefighters, each with 10 to 25 years of firefighting experience. The modules mapped aerial drop activity and recorded incident objectives, outcomes, and conditions for aerial suppression actions that supported tactical and strategic incident objectives. The module coordinator coordinated crew movements.

AFUE personnel applied analysis protocols to data after observing 27,611 drops from 2015 to 2018 at incident locations throughout the USA in 18 States and across all nine Forest Service regions.

Other studies

This was not the first time that a study took on the task of determining the aircraft mix needed to assist wildland firefighters in the United States or to evaluate aerially applied fire retardant. The Inspector General’s report listed seven, most of which are on the Wildfire Today Documents page.

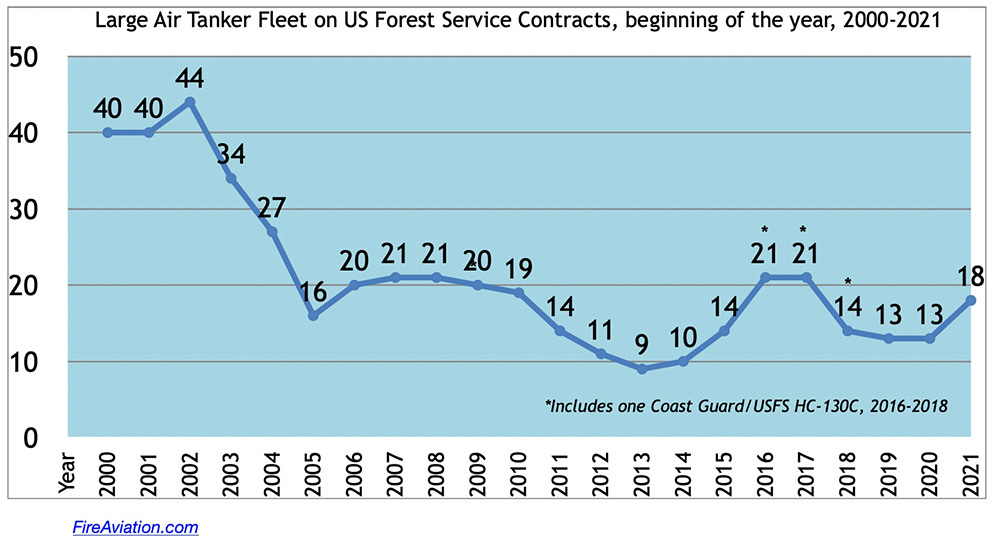

1995, National Study of Airtankers to Support Initial Attack and Large Fire Suppression: Final Report Phase 1, recommended 41 large air tankers.

1996, National Study of (Large) Airtankers to Support Initial Attack and Large Fire Suppression: Final Report Phase 2, recommended 41 large air tankers.

2005, Wildland Fire Management Aerial Application Study, recommended 34-41 large air tankers.2008, Management Efficiency Assessment on Aviation Activities in the USDA Forest Service, recommended 19 large air tankers.

2009, National Interagency Aviation Council Interagency Aviation Strategy, recommended 32 large air tankers, 3 water scoopers, 35 single engine air tankers, 34 large helicopters, 47 medium helicopters, and 100 small helicopters.

2012, Air Attack Against Wildfires: Understanding U.S. Forest Service Requirements for Large Aircraft, Rand, recommended 1-9 large air tankers, 14-55 water scoopers, and 0-7 large helicopters.

2012, Firefighting Aircraft Study, AVID LLC, recommended 35 large air tankers.

Additional studies not mentioned in the Inspector General’s report:

1984, Project Aquarius was designed to test the effectiveness of large aircraft in controlling bushfires in Australia by dropping water and fire retardants, but also to research the nature of wildfire, its effects on the bush and the firefighters, and the most effective forms of fire control. It was not fully completed.

1985, Operational Retardant Evaluation, USFS.

2007, The Effectiveness and Efficiency of Aerial Firefighting in Australia, Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre.

Which fires were analyzed in the AFUE study?

The fires at which data was collected were primarily large that escaped initial attack, since it takes time to mobilize the modules. Smaller fires that were stopped by ground and air resources are likely underrepresented; that is, fires on which aircraft were most effective may not show up in the data. Fires burning during high or extreme fire danger that grew large because of the burning conditions may be overrepresented. As conditions become extreme, firefighting aircraft are less effective.

From the study:

[T]he sample may be biased towards incidents with substantial aircraft activity and especially those with any airtanker activity. Because AFUE was launched primarily to evaluate large and very large airtankers, choices were consistently made to observe fires with airtanker activity. Recognizing that many fires that receive any airtanker drops typically only receive a few drops, the sample could be underrepresenting fires with limited airtanker activity. Further, many aerial firefighting drops occur on remote fires that make direct observation challenging.

What were the findings of the AFUE?

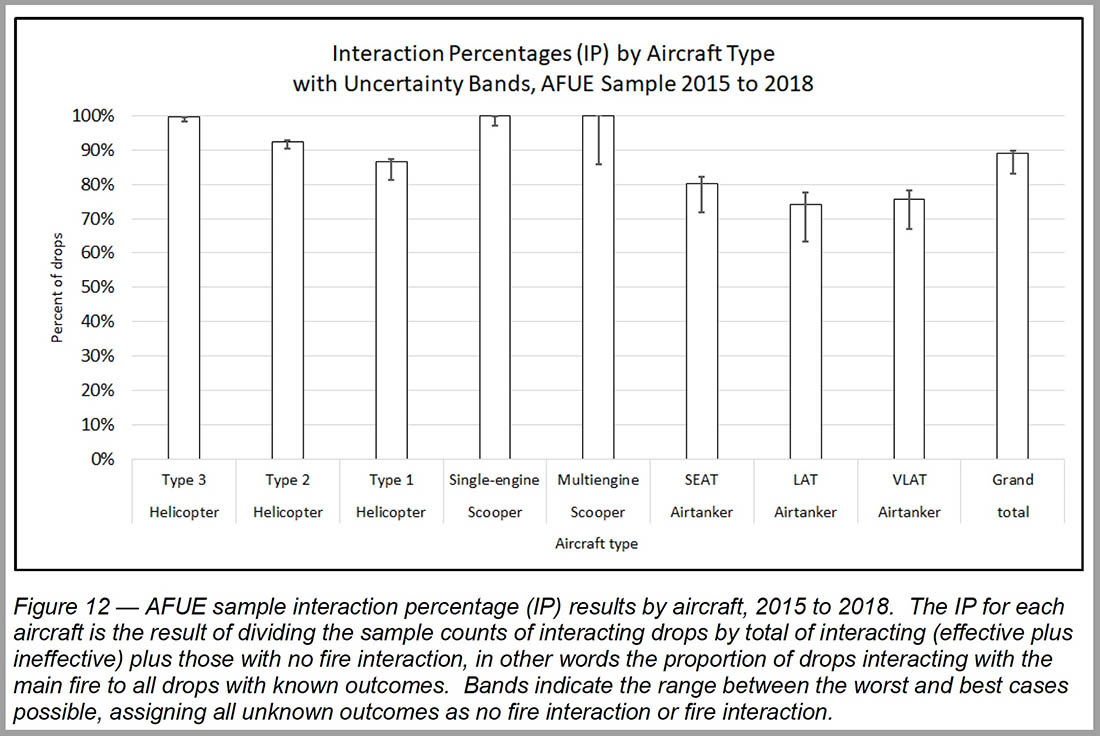

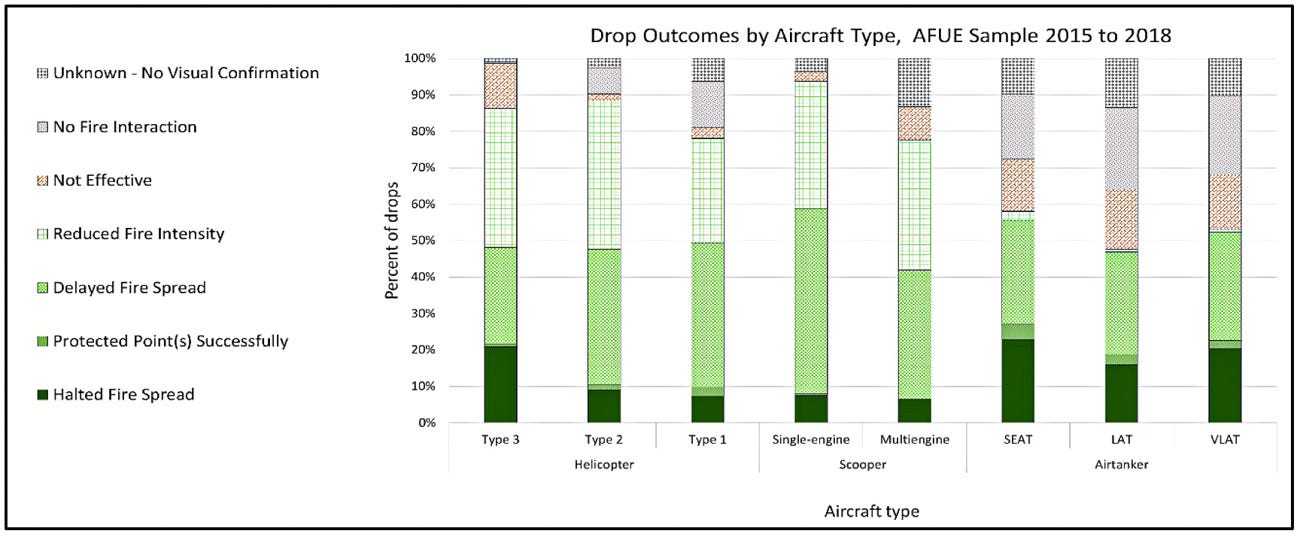

Much of the AFUE report is based on two performance measures that the study used to determine the effectiveness of an aircraft, Interaction Percentage (IP) and Probability of Success (POS). IP, a term apparently invented, is defined as the proportion of drops that interacted with fire. POS is the number of effective drops divided by the total number of drops with known and interacting outcomes.

The interaction percentage data compares apples and oranges. Helicopters and scoopers primarily drop water, while fixed wing tankers that are not scoopers almost always drop long term fire retardant. Since water is a very short term fire retarding agent, it is usually dropped directly on the flaming front. If it were dropped out ahead of the fire, much of it would run off the fuel, soak into the ground, or evaporate before the fire reached that location.

Long term fire retardant dropped by air tankers is usually placed ahead of the fire. It might be dozens of feet away, or when pretreating a ridgeline, protecting a point, or securing a planned indirect fireline it could be thousands of feet away from the flaming front. Retardant, much more viscous than water, adheres to the vegetation more so than water, retains moisture for a while, and can even interfere with the process of combustion after it dries.

Therefore, comparing the interactions of water dropping and retardant dropping aircraft is not a reasonable exercise. Water droppers should always be very close to 100 percent on the interaction scale, while retardant droppers will have lower numbers, in part because some of the drops are done to support indirect firelines or ignition operations that did not interact with the main fire.

The chart which shows small Type 3 helicopters having 100 percent interaction does not mean that dropping 100 gallons of water is going to have a larger overall fire-slowing result than a 75 percent interaction DC-10 very large air tanker dropping 94 times as much liquid.

The interaction rates of single engine, large, and very large air tankers all range from about 74 percent to 80 percent. And in the helicopter category, it is about 87 percent to 100, with the small 100-gallon Type 3 having the highest number. The largest Type 1 helicopters carry 2,500 to 3,000 gallons; their interaction percentage is about 10 points higher than the average retardant dropping air tanker.

The study also rates the aircraft on the probability of success, only taking into account drops that actually interacted with the fire. When used on a large fire the helicopters averaged about 0.73 and the retardant dropping air tankers, about 0.72. If excluding the small Type 3 helicopters which are not often used to drop water on large fires, the helicopter average increases to about 0.84

What did the AFUE study recommend?

The AFUE made no recommendations. There was no strategy identified to configure a national firefighting aircraft fleet. It did not summarize to say we need X number of single engine, very large, or large air tankers, or X number of Type 1, 2, or 3 helicopters. Nor did it break down effectiveness by model of aircraft or vendor. It only sorted the data by general size of the platform.

Since making recommendations about the size and composition of the aircraft fleet was one of the most important objectives, the refusal to accomplish this is a significant failure. Other deliverables of the project were supposed to include recommendations regarding: program standardization; operations; risk management and safety; best management practices; cost effectiveness; and the development, implementation, standardization and quality assurance of aerial firefighting aviation operations.

What about cost?

When a federal agency spends more than half a billion dollars in a year on one activity such as fire aviation with very little meaningful oversight, it needs to have a robust knowledge base for making decisions about how to spend those taxpayer dollars.

A search through the 46 pages of the AFUE study for the words “cost” and “dollars” — found nothing.

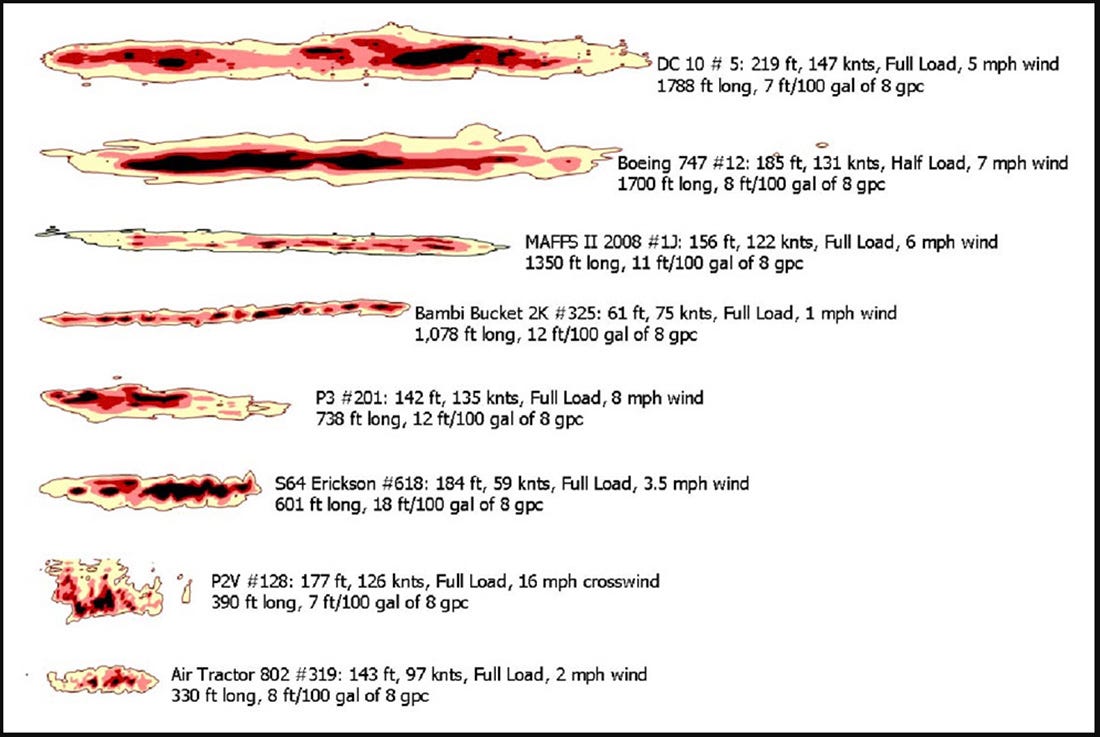

There are many variables that affect the number of gallons per day that an aircraft can drop on a fire, including the aircraft’s speed, range, distance to reload and refuel, drop capacity, and time required to reload and refuel.

An analysis tool was created recently by an independent organization that scrutinized the characteristics of eight models of helicopters, seven models of large and very large air tankers, and single engine and twin engine scoopers. Comparing all 17 aircraft, it can display delivered cost per gallon, drop cycles per day, and gallons delivered per day. More time spent on developing this tool would result in additional worthwhile information. I have seen and used the interactive analysis system but do not have permission to fully publish it. In fact, I and others had a small part in evaluating and fine-tuning the system. Using the variables above, and more, it found that for example where the fire was 100 miles from a retardant base the cost per delivered gallon of retardant by a large or very large air tanker varied by up to 100 percent. Of the large and very large air tankers, the VLATs were the most cost effective, while two 3,000-gallon tanker models were twice as expensive. Others were in between. The helicopters and single engine air tankers were considerably less expensive per gallon, about 30 to 60 percent of the cost of the least expensive large or very large air tanker. And in some cases, depending on the aircraft, they did not have to fly 100 miles each way to refill with water, fuel, or retardant, which was factored into the results. In the example scenario a scoopable lake was 15 miles away and a helicopter dip tank was within 6 miles. These numbers could vary wildly from fire to fire. I believe the analysis did not include the cost of retardant, just the costs of fuel and the hourly and daily rates of the aircraft.

Is size important?

While the AFUE study did sort the results by the general size of the aircraft, it did not consider the importance of the quantity of retardant or water, or the relative effectiveness of 100 gallons from a Type 3 helicopter vs. 3,000 to 17,500 gallons from a large or very large air tanker.

There are times on a fire when you only need a relatively small amount of aerially delivered water or retardant — for example, a one-tenth acre fire with a slow rate of spread; a single lightning-struck tree; to support line construction or burning out on a small fire which has stopped spreading; or a quiet Division on a large fire. Small helicopters can also be used for non-direct suppression tasks, such as intelligence gathering, supervision, or reconnaissance. In those cases, a Type 3 helicopter with a 100-gallon bucket might be ideal. Similarly, there are times and places for small, large, and very large air tankers. Firefighters need an assortment of resources in their tool box.

If a fire is aggressively expanding and has the potential to destroy valuable resources or threaten lives, an attack with overwhelming force is the best choice, possibly saving money by keeping a fire from turning into a megafire that could cause evacuations, fatalities, or cost tens of millions to suppress. An aggressive initial attack with high-performing aircraft supported by an adequate number of firefighters on the ground can also reduce or eliminate the long term exposure of hundreds or thousands of firefighters to unnecessary risks while battling a huge fire that could go on for months. This becomes even more crucial during a pandemic.

What is next for the AFUE?

According to USFS Acting Public Affairs Specialist Deb Schweizer data for the study was collected through 2020, but only data from 2015 through 2018 was used in the report released in August, 2020.

I asked Ms. Schweizer if the rumor is true that the AFUE is being shut down and if additional reports will be released.

“No other reports are planned for the AFUE at this time,” Ms Schewizer wrote in an email. “However, the Forest Service will continue to utilize AFUE findings in processes of planning, assessment, monitoring, and feedback for fire managers who establish operational plans, request aircraft, and order drops to achieve tactical missions.”

Asked again if the AFUE is being shut down, and what the plans are for continuing the study, she replied, “Our goal for AFUE at this time is to develop and implement performance measures, support evidence-based resource deployment decisions, and inform strategies for future aviation budgeting and contracting. This effort will enable the Agency to monitor, learn, and adapt to changing conditions and to ensure financial viability while also maintaining a high degree of operational effectiveness.”

Ms. Schweizer did not reply to our question, “Will additional data collection in the field occur this year?”

Comments on the AFUE report from aerial firefighting subject matter experts in the government and private sector

Some of the quotes below that we solicited about the AFUE report are from people who are not authorized to speak publicly about the report, or do not feel comfortable having their names disclosed.

Tom Harbour

(Mr. Harbour was the USFS Fire and Aviation Management Director when the AFUE was initiated. He is now a consultant for Perimeter Solutions.)

AFUE was intended to follow on, and enhance, studies of aviation which had been done previously (e.g. ORE, etc).

“AFUE was initially intended to eventually help answer questions about the size and composition of aviation assets needed by the USFS. My hope was that the combination of AFUE and other fire planning tools would bring analytical rigor and expert systems together to allow a more disciplined look at overall allocation as well as forming a basis for trade-offs both within the agency and ultimately on an interagency basis.

“I knew that in order for the AFUE study to complete its intent, the study would require investment and time. The complexity of critically analyzing the USFS FAM aviation program, let alone accounting for, and effectively integrating other interagency assets, has stymied various fire planning systems for decades. A process and procedure which works reasonably well in one part of the country or for one agency has significant flaws in another. I expected AFUE to have growing pains. I felt the need to collect good data was, and is, a sound basis for any sort of subsequent analytical conclusions which would be drawn. AFUE was staffed and led by people who were focused on answering key questions.

“While I have no specific “inside” information, it is safe to assume that USFS leadership and Congress still need answers to critical aviation questions. Those answers must be based on science, facts, and correlation with “expert systems” (what the experts know).

“The current AFUE publication drew some interesting conclusions, but obviously does not have specific recommendations about types or specific numbers of aircraft. Each of us in wildland fire, from our experiences, have our own “favorites” in the mix of the various types of fixed and rotary wing aircraft available to us. Our own bias causes us to believe we need more or fewer of this type of aircraft. The debate goes on. However if AFUE has set a basis for answering questions whether in the context of direct “lessons learned” or conversely has provided a basis for determining an unproductive line of reasoning, it has achieved a measure of success. We would all agree we need data to substantiate conclusions.

“Many complex problems are not solved in their first iteration (e.g. NFMAS, FPA, etc). but provide useful approximations for future work. In that context, I’m content to leave the overall assessment of the AFUE report to USFS and interagency leadership. They are the ones who are faced with the barrage of questions about specific aircraft and the effectiveness of those aircraft. They are the ones who make the trade-offs about “cost benefit ratios” and “return on investment”. They are the ones who deal with constrained budgets. They are the ones who are forced to face the difficult questions AFUE was intended to help answer.

“Finally, I know those leaders are conscientious stewards of the taxpayer funds.”

Ryan Becker

(Mr. Becker was the USFS Project Manager of the AFUE during most of the study. A mechanical engineer, he now runs a consulting business focused on aerial firefighting.)

“The intensive field data collection effort was shut down and no work was invested in creating a true field data collection protocol that would have obviated the need for the dedicated crews as we had proposed. I have heard that the leader of AFUE’s analysis efforts continues to work with the data and hopes to have more released.

“What the agency is really missing out on is the contributions with established wildfire research programs, such as UCSD, SDSU, SJSU, UCSB, and the University of Montana and others would happily make for free.

“The data collectors worked longer, harder seasons than the busiest hotshot crews or ATGSs. They deserve far more respect than the agency ever gave them. I did my best, but they just fell into this black hole where they relinquished their operational positions to support Aviation without becoming a part of the Aviation organization. They weren’t working under Research, nor was it a permanent Technology and Development program. We could never get people to adopt a label for the program that they would accept as legitimate.”

Person #1

“In terms of helping the government to select what type of aircraft mix, for what areas etc. I personally believe the mark fell dramatically short. As often with these types of large style macro studies, the finite details and data were withheld — perhaps for future reporting and reporting out?

“One would think that more reporting and data would be coming out in the near future, or perhaps the widespread availability of access to data for incident use. However navigating that shipping lane, even with fire director fire power behind you, has been uneventful at best.

“What will the fleet look like? Honestly I believe it will be what industry tells us it will look like. Reading this report, not one operator would be able to deduct or navigate what the next best thing for fixed wing retardant will be.

“As it was relayed to me, the AFUE was abruptly shut down and the comment that individual made was ‘We had so much more to share, data papers, info, and we cannot share any of it.’ ”

Person #2

“It’s not a bad start, some useful observations – but where’s the rest of it?

Acknowledging the AFUE stated mission is certainly quite limiting, I think that more was expected – maybe it’s still coming? The project must have collected a bunch of data – what are the opportunities to keep analyzing and seeing what other insights can be gained?

“IP and PoS could be useful measures going forward, but they only tell part of the story (and not quite sure how they will resonate with field users of aerial firefighting – but maybe that doesn’t matter if the focus is overall fleet design).

“Defining descriptions of task work assignments and standard descriptions of drop outcomes is useful and could potentially be used as a basis to continue to collect useful data going forward (e.g. from ATGS’s) – though there may be some discussion to be had about refining these descriptions a little – and wouldn’t it be great to get this sort of assessment framework standardized nationally and internationally.”

Person #3

“LATs and VLATs are very rarely assigned to drop directly on fire, such that AFUE would have recognized the mission as having ‘interacted with fire’. However, LATS and VLATS do drop very near the fire where the fire does often interact, especially during initial attack. The study of initial attack is marginalized here due to the AFUE team’s focus on large well established fires, where existing data substantiates their effectiveness. That’s very often different than the helicopter, scooper, or SEAT mission where IP is always a given on large fires, where water is employed in direct support of fire fighters on the ground. It is, therefore, a flawed report because the large air tankers were assessed based on mission protocols to which they rarely (if ever in the sampling used) were assigned to drop directly onto fire. It’s important to remember that helicopters are multi role capable and there are hundreds of them available, as opposed to a few airtankers. 40+ EU helicopters, which are needed when fires get big and get away.

“Why would the report focus on fires that had already grown large? Rapid initial attack and extended attack before fires explode into huge fires is the core mission of LATs and VLATs for sure, and to a degree all platforms. The Report essentially confirms a lack of USFS understanding of how aerial platforms SHOULD be used.”

Person #4

“It supports and confirms the RAND report from 2012 that recommended a greater reliance on scooping aircraft. We were surprised to see the Forest Service coming to that conclusion, AGAIN. How many more expensive studies are needed for them to conclude that they should be using more scooping aircraft? The report also comes up short in recommending what the mix of aircraft should look like going forward and anything to do with the costs of each platform. Add cost indices to this analysis and the story would be even more compelling for certain scooping aircraft.

“Since the federal aerial firefighting fleet works under SBA Carve Outs based on unnecessary/outdated NAICs codes size requirements, the industry does not have the economic attractiveness to bring more investment capital into the space to provide a large enough fleet that is technically advanced and safe enough to allow us to make this a fair fight with Mother Nature. Combine that fact with federal fire agencies’ growing reliance on CWN contracts and it’s like showing up at a gun fight with a knife. If this trend is based on costs, then wouldn’t more cost and fire effective aerial assets make sense? This report provides the road map to reduce costs and achieve better outcomes, will they follow it?”

Our take

After 9 years, spending more than an estimated $11 million taxpayer dollars, and analyzing 27,611 drops, we have a right to expect more than charts illustrating questionable criteria that treat all aircraft as having the same production rates.

All of the raw data and any additional reports that have been written should be released. If it is going to be kept secret, we need to know why. What is it that the government does not want us to know about aerial firefighting?

The information that was collected over nine years came at enormous cost to the taxpayers and considerable effort by the 12 field personnel. The very limited amount of information released to date does not justify the cost. While collecting the data was hard, analyzing it while sitting in an office is not easy either. As Mr. Becker said, the data should be made available to experts and institutions who can comb through the numbers and make informed recommendations. They could begin to actually answer questions about the “size and composition of aviation assets needed by the USFS,” as Tom Harbour described one of the original intended goals.

The data should be able to compare individual models of aircraft and even vendors with similar aircraft. It presumably has data that can analyze the differences in effectiveness and drop patterns between gravity retardant tanks and those that are pressurized. It could cipher out load and return times, gallons delivered per hour or day, and the cost of a delivered gallon — based on real world data.

Combined with weather and fuel information, the trove of information could quantify how weather and fuel conditions affect the effectiveness of dropping liquids onto fires. For example, above a certain identified threshold, certain aviation tactics will not work, so don’t waste time, money, and exposure of the flight crews. Firefighters have general ideas about this, but developing it into something that could written down, would be helpful. The results could be referenced when the public or politicians ask why the sky is not filled with firefighting aircraft whenever there is a smoke column visible. (“Our firefighting experience and a study showed that with the conditions on this fire today that aerially applied retardant or water could not be effective. In addition, the strong gusty winds make it too risky for our pilots flying low and slow, and for the firefighters on the ground.”)

The data, when analyzed, could be part of a solution about where, how many, and which type of aircraft to stage and deploy based on conditions, including fuel moisture, fuel type, current and predicted weather, reload or scoop sites, and if the likely dispatch is initial attack or larger fire support.

In 2020 the number and size of wildfires burning in the west far outstripped the number of ground and air firefighting resources that were needed. On September 19, according to NIFC records, 32,727 personnel were committed to fires. That was the highest number since August 24, 2015 when 32,300 were deployed. Many fires were severely understaffed, and some had to be left to burn for a period of days. Incident Commanders who were requesting aircraft were too often told none were available. In conditions like we have seen in recent decades, fire agencies, including those who mostly grow trees, should be extremely confident their aerial fleets are comprised of the most capable aircraft in adequate numbers so that all wildland fires that are being suppressed can be attacked from the air within the first 20 minutes, supporting firefighters on the ground.

This is just basic Homeland Security.